Anywhere where there are bodies of water, next to oceans, lakes or mountain rivers, there exist communities who define themselves as fisher communities. For thousands of years, they have survived off catching fish, but have also created practices, rituals and norms centred around fishing as a cultural identity. These practices also contribute to conserving this important resource.

Fish feed three out of every seven people on the planet and is a main source of protein for more than 3 billion people. Yet, indications are that nearly 90% of our fish stocks have been depleted, according to a 2016 report by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. While this represents a threat to the way of life for the fisher communities, there are other threats that need to be considered. In fact, while indigenous communities are now seen as the key to conservation of natural resources, ironically, they are often excluded from the places where they accessed these resources – in the name of conservation.

National policies around quotas

In South Africa, the quota system has always favoured the large-scale commercial fishing companies, resulting in small-scale fishers, who have been fishing for many generations, being given an unfair allocation, which severely impacts their ability to earn a livelihood from fishing. Many have turned to poaching, and many have died in the process. Even with the development of a small-scale fisheries policy, racial discrimination has resulted in traditional fishers being excluded from fishing in certain areas. This had to be challenged in the courts.

Excluding traditional fishers, who practice sustainable harvesting practices, from accessing their customary resources fish through skewed or discriminatory quota systems will simply result in fishers employing illegal tactics in order to harvest fish and thereby criminalise customary practices. This means that authorities will have an even more difficult time conserving fish stocks and will prevent them from having oversight of fish catches. They will also expend valuable resources on “policing” the oceans, instead of using these resources to conserve the resources.

Marine Protected Areas

Throughout the world, Marine Protected Areas have been established to protect marine life, ensuring that fish nurseries and other vulnerable marine ecosystems are kept intact and the sustainability of the marine ecosystem is ensured. But MPAs have also been known to exclude traditional fishers, and even criminalise them. Without recognising and including traditional fishers in the management of the MPAs, a similar situation will occur as with quotas – communities will simply fish “illegally”. Other communities will turn to non-traditional means of getting an income, forced to sink or swim in a regulatory environment that doesn’t recognise their cultural rights, nor their contributions to conserving the resource.

Fishing communities should not have to resort to criminal acts in order to benefit from their cultural practices and sustain a livelihood. How do we include them?

Supporting struggles for environmental justice

A significant case in South Africa is leading the way towards recognising the rights of traditional fishers in the country. In Dwesa-Cwebe in the Eastern Cape, the community was deprived of their access to natural and marine resources through the establishment of an MPA with a no-take policy. After David Gongqose and his co-accused were arrested for fishing, social justice organisation, the Legal Resources Centre went to court to defend them on the grounds that they were practicing their custom of fishing.

To the delight of local customary law experts, the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) ruled that they had a customary right to fish there. In summing up the impact of the case, GroundUp found that, “The case is possibly the first time a customary right has been used as a successful defence against criminal liability. It is also the first time [that] courts have described the test to decide whether legislation has removed customary rights. The harmony that the SCA found between customary rights and sustainable development is also novel. It will have far-reaching consequences in the environmental sector and for the rights of rural communities.”

This case will certainly have an impact on the communities that Natural Justice are working with in South Africa. Specifically, Natural Justice are working with the West Coast community of Guriqua to develop their biocultural community protocols (BCPs). BCPs are an embodiment of the cultural values and identity of a community and can enhance their customary protections and clarify their relationship with their resources. During a one-day workshop in 2017, the Guriqua shared that their ancestors had lived and fished in their Cedarburg coastal region for centuries. They have sustainably fished and protected the natural environment during this time.

With the development of the Guriqua BCP, the community will have a tool which gives them a unique position from which to conserve their resources based on their cultural practices. It could also be the basis from which the community can legally defend themselves in the event that they are criminalised for harvesting natural resources in the area. The BCP has the capacity to breathe life into any broken or diminished cultural practices.

With the precedent in the SCA now set, the community will have greater recourse to the law to recognise their customary rights. Because of this, together with policy changes in the country, including a Small-Scale Fisheries policy, we can move away from criminalisation to recognition, bringing dignity to fishers and ensuring the sustainability of a depleting resource.

In Kenya, a different type of threat is putting the livelihoods of coastal fishing communities at risk. The Lamu Port Development (and the expected development of the Lamu Coal Plant) is already having significant negative impacts on fish stocks and the concomitant local fishing industry which provides for approximately 4734 local fishers. The fish population in the area has already decreased as the Port Development has increased the water turbidity. The fishers have been displaced from the ideal fishing spaces and their catch sizes have been reduced. The Port Development impacts will be compounded by the development of the coal plant, which will raise water temperatures and risks; significantly polluting the local marine environment, including mangrove forests. This will further deplete fish stocks and may spell the end of local fishing in the area.

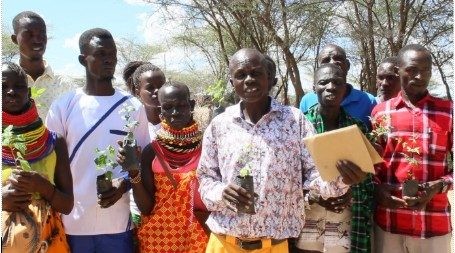

But local fisher communities are fighting back, and in the case of Kenya, using the courts as a tool for challenging lack of environmental compliance and consultation; while also seeking to protect their livelihoods (and local fish populations). Through community organisation, Save Lamu, and with help from the Katiba Institute and Natural Justice, the community went to court. The basis for their application against the Port Development tackled the unconstitutional nature of the development, as well as the lack of community consultation. It took six years, but in May this year, in a historic judgment with repercussions for other Kenyan traditional communities, the court found in favour of the fishers. While compensation of 1.7 billion Kenyan Shillings (17 million USD) was awarded to the fishers for the infringement on their traditional fishing rights, it was also the recognition of the importance of public participation in the formulation and execution of development that will be crucial to the future of Kenya. It was also the first time a court in Kenya recognised traditional fishing rights.

This World Fisheries Day, we look to these case studies with hope. In South Africa and Kenya, we can show that recognising traditional rights is one of the best ways to protect the future of marine resources. Instead of criminalising fisher communities, excluding them for the benefits of conservation and refusing to engage with them around developments that affect their livelihoods, governments should see them as custodians of our marine resources and important players in conservation.