On 16 and 17 October 2023, Cape Town hosted the 2nd South Africa Green Hydrogen Summit. The Summit aimed to showcase South Africa’s potential as a green hydrogen producer and exporter. Natural Justice attended the Summit with H2 Watch, representing the interests of communities and Indigenous people, to voice concerns about South Africa’s rush to develop green hydrogen.

This development must not happen without adequate public engagement and dialogue about: who benefits, what the plans are for the roll out of Green Hydrogen (GH2), who will bear the environmental and social burdens and how those burdens could be avoided or minimized through robust public consultation and social and environmental safeguards. During the Summit, H2 Watch released a statement, supported by Natural Justice, which spoke to these concerns.

The Summit

The Summit was sponsored by Sasol, Anglo American, GIZ, BMW, Eastern, Western and Northern Cape Government, Industrial Development Cooperation, Siemens Energy, Engie and Development Bank of Southern Africa. This represents a sample of the types of companies and government entities that are seeking to invest in and profit from hydrogen production in South Africa. These companies and the government representatives steered and influenced the agenda of the Summit. Only two sessions spoke to the participation and impacts on communities.

Governments have been encouraging GH2 as a new fuel source, both for the export market and to power difficult-to-electrify sectors in South Africa, such as mining and heavy industry. In South Africa, Green Hydrogen facilities are being pushed urgently through the Green Hydrogen Commercialisation Strategy and in the locations of Boegoe Bay, Saldanha Bay, Vaal, eThekwini and Richards Bay. These projects are all at beginning phases.

Green Hydrogen – What is it

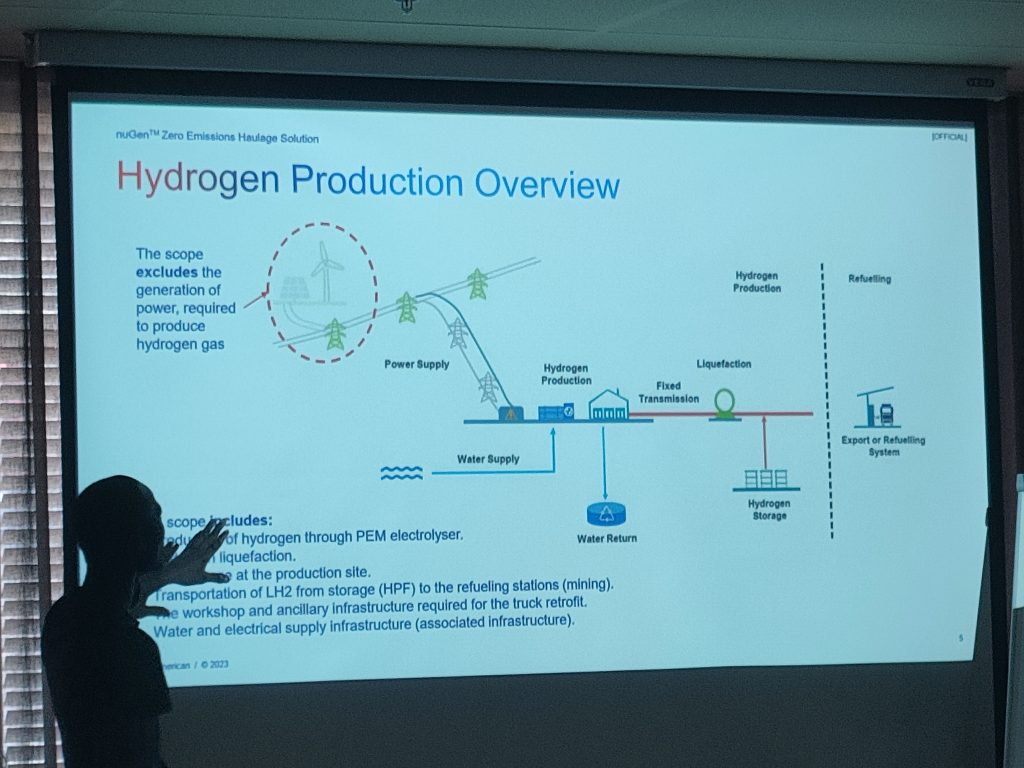

GH2 is produced through a clean process using electrolysers to split water molecules – but this is done with renewable energy – which is why it is considered “green”. At the Summit, one stand had a small example of the process of creating GH2. It burns cleanly, emitting only water vapor. It is an energy vector, or carrier, that can be used for long-term energy storage and then supply that energy later with no carbon dioxide emissions during combustion. There is also grey hydrogen made via a dirty process using fossil fuels like gas, oil and coal during the process, and blue hydrogen which is produced from gas with the use of capture and storage of carbon dioxide emissions.

Uses of Green Hydrogen

Green Hydrogen may be a game-changing solution for decarbonising heavy industries (i.e., cement and steel), shipping, heavy transport and mining. GH2 can also be a critical tool to balance the electricity grid with increasing shares of variable electricity generation from wind and solar. Too often, when there is excess solar and wind power generation on particularly sunny or windy days, the excess can’t be used or stored, so the grid operator requires the generator to turn off, or curtail, its electricity generation. That excess generation could be used to produce GH2 that then could be stored for future use.

Going forward

Concerns that must be addressed before South Africa goes further down the green hydrogen path

Green hydrogen will be used to justify grey and blue hydrogen

There is concern that governments and industry will push to continue the use of grey hydrogen and expand use of blue hydrogen to build the market for the much-hyped GH2 future. It is impossible to tell how hydrogen has been produced as a molecule of grey hydrogen looks the same as a molecule of green hydrogen. So, traceability, or guarantee of origin requirements, are critical. Without proper requirements, there is worry that major oil and gas companies will use green hydrogen to look environmentally friendly, while still continuing with fossil fuel-based hydrogen (what we call “greenwashing”).

IRENA stated that at the end of 2021, only 1% of hydrogen was produced with renewable energy with grey hydrogen being almost 99% of all hydrogen produced in the world. According to the IEA, in 2018, 76% of hydrogen produced was from natural gas and the balance was from coal. It’s important to underline that blue hydrogen is not a climate friendly alternative to grey – it produces only 9 – 12% less carbon emissions than grey hydrogen with higher fugitive methane emissions. (Methane is reported by United Nations Environmental Programme to be 80 times more potent in terms of a climate warming pollutant than carbon dioxide, during a 20 year timeframe.) There are serious concerns that plans for the GH2 future will be used as an excuse to expand the market for blue hydrogen in the near term, which would be bad for the climate and give a lifeline to gas production that is not economically viable, that is being outcompeted by renewable electricity generation.

As Bruce Buckheit states in the report “Deconstructing the Hype on Hydrogen Hubs”, the use of grey and blue hydrogen will result in higher carbon emission levels. Therefore, unless it is green hydrogen, hydrogen production is not a solution for energy transitions to lower carbon emissions.

Impacts on communities, the public, and South Africa’s energy crisis

Throughout the Summit, concerns were raised about diverting renewable energy generation from the grid to GH2 production – energy that could be used to lessen South Africa’s electricity crisis (including load shedding, or blackouts, and energy insecurity). Green hydrogen production requires energy and it takes more energy to produce green hydrogen through electrolysis than hydrogen produces when it’s combusted.

In terms of local communities and indigenous peoples, there are serious concerns about land and water. To produce vast quantities of GH2 requires a vast amount of renewable energy, and, in turn, a vast amount of land for solar and wind farms, for example. In South Africa, there has been a failure to redress land inequalities following the enactment of racial land legislation during apartheid. This has left many local communities with land rights insecurity. Green hydrogen’s need for land can threaten this land security further.

GH2 requires a vast amount of clean water – a resource which is scarce in South Africa and threatened due to climate change. Should local reserves of water be used, this will impact the access to water of communities. This includes communities in desert-like regions such as the North Cape. Should water be provided through desalination plants, fishing communities may be impacted by the brine that may pumped back into the ocean.

The potential conflict over land and water must be addressed through meaningful public consultation with local communities and Indigenous people, in Environmental Impact Assessments and other processes, as well as community benefit arrangements, to ensure that social, cultural and environmental safeguards are respected, and communities’ and local livelihoods benefit from job guarantees, reduced electricity prices, and critical infrastructure projects.

Moving forward: Regulations for Green Hydrogen

To address the above concerns, regulations should be put in place before moving forward with GH2 commercialization, including:

- Hydrogen certification: Clarifying the definition of renewable/ green hydrogen to facilitate certification/Guarantee of Origin.

- Guarantee of origin (GO) schemes being set up and implemented.

- Setting local job creation and poverty alleviation targets alongside the hydrogen value chain.

The Future of Green Hydrogen

Green hydrogen in South Africa has potential for job creation, for improving economies and the decarbonisation of certain sectors of the economy. However, this needs to be done through meaningful consultation with civil society, communities and Indigenous people (which must be continuous and throughout all stages of the project, including implementation) with strong guarantee of origin regulations to help ensure that South Africa’s GH2 programme doesn’t end up creating a new market for gas-based blue hydrogen in the near term, undermining the nation’s climate goals.

Resources:

- A press statement from H2 Watch can be found here. Links to recordings of summit sessions on community participation and how industry should engage with communities, can be found here.

- The programme and recordings of the different sessions of the Summit can be found at SAGHS 2023 | Green Hydrogen Summit.

- RMI report “Fuelling the Transition: Accelerating Cost-Competitive Green Hydrogen” and the Carbon Tracker report “Clean Hydrogen’s Place in the Energy Transition”.