On Wednesday, 2 November at the 7th Working Group on Article 8(j) and Related Provisions (WG8(j)), Natural Justice co-hosted a side event with the Union of Indigenous Nomadic Pastoralist Tribes of Iran and the ICCA Consortium entitled, “Recognizing and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities”. It included a number of presentations from Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ experiences and lessons learned with the recognition and support of ICCAs in different contexts.

Territories and areas conserved by Indigenous peoples and local communities (also known as ICCAs) are a phenomenon of global significance for the earth’s biodiversity and ecosystem functions, cultural and linguistic diversity, and livelihood security. If appropriately recognized and supported, ICCAs could account for the conservation of as much land and natural resources around the world as those currently under government protected areas. Since 2003 and 2004, respectively, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the CBD Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA) have stressed the need to better understand and appropriately support ICCAs. CBD Decision X/31 also calls upon Parties to recognize the role of ICCAs in biodiversity conservation, collaborative management, and the diversification of protected area governance types.

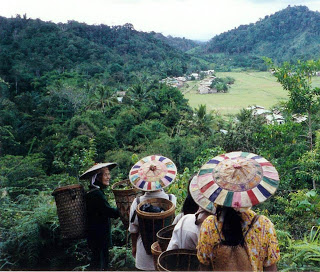

Taghi Farvar (Union of Indigenous Nomadic Pastoralist Tribes of Iran) opened the side event by providing an overview of the global phenomenon, significance, and international recognition of ICCAs. Onel Masardule (Fundación Para la Promoción del Conocimiento Indígena, Panama) described the intrinsic connections between Indigenous peoples, nature, and territories and the role of ICCAs (or locally named equivalents) as alternatives to state protected areas that provide an opportunity to reclaim control over ancestral territories, strengthen traditional authorities, and recognize rights and local priorities.Anchalee Phonklieng (IMPECT, Thailand) illustrated customary understandings and management of sacred areas in Karen territories. Some areas and plant and animal species have strong taboos associated with them and require strict observance of ceremonies and rituals, which in turn, help stimulate the community’s commitment to taking care of these areas and species. She noted that national policies created a derogatory sense of “primitiveness”, but that her community is now more aware of the multiple values of their customary practices, including in conserving biodiversity. She also highlighted the importance of having a strong education system to pass on knowledge, practices, and beliefs to younger generations.

Thora Martina Hermann (University of Montreal) spoke about the Naskapi First Nation legend of the Caribou Heaven and the process of recognizing it as a sacred area in a new national park in Québec. The designation was proposed by the Naskapi Elders Advisory Council and the Council of the Naskapi Nation and included a recommendation that an elder always be a member of the management committee and that cultural information be included in educational materials. A number of mining projects in northern Québec as well as the proposed establishment of 15 new national parks on Indigenous territories led to the Naskapi and Cree Nations calling together for all Indigenous sacred sites to be recognized as such in national parks. She highlighted the complexity of working within multiple jurisdictional layers of protected area legislation.

Jocelyne Garrett shared the experiences of the Brokenhead Ojibwe of southern Manitoba, who wanted to protect the rare wetlands in their ancestral territory from external threats such as mining. After a process of community-based research that combined Western science and traditional knowledge and 8 years of negotiations, the area was designed an Ecological Reserve, the highest form of environmental protection in Canada. The Ojibwe still have access to sacred areas and medicinal plants, among other things, and manage the Reserve in partnership with Manitoba Model Forestry and Native Orchid Conservation. They were recently awarded $1 million to build a boardwalk in the Reserve to mitigate tourism pressure upon the sensitive wetlands. It was noted during discussion that each society has a cosmovision that gives rise to a scientific system and that equitable valuation of those systems is an essential part of respecting customary governance and management systems.

Gunn-Britt Retter (Saami Council) described the situation of the Saami in Norway, saying that respect for traditional management in the northern areas has decreased because of increasing demand for energy and resources, extraction of which is moving north due to the majority of the south being privately owned. She noted that the Saami people are literally being squeezed “from all sides”, with an increasing number of mines, state-governed protected areas, wind mills, and other developments encroaching steadily into their customary territories and rangelands. Lamenting the fact that the Saami have achieved significant recognition of cultural heritage rights, including language, but not yet secure land and resource rights, Retter emphasized that territory is the absolute foundation of Saami culture. Though discontinued and apologized for several years ago, she highlighted the state’s official Norwegianization policy as responsible for the continuing “colonization of the mind” and the general sentiment of “to be Saami is to be oppressed”. Citing lack of participation as the main reason for generally rejecting new state protected areas, the Saami Parliament may now consider establishing their own protected areas according to customary management systems. Questions remain about how to determine boundaries amidst pressure from mining companies to snap up unclaimed land.

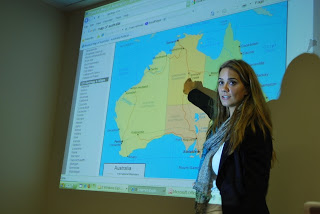

Eloise Schnierer (Watego Legal and Consulting) described the overall legal context and intricacies of realizing Indigenous peoples’ rights in Australia, including the Native Title Act, the Torres Straight Regional Seas Claim and Blue Mud Bay Decision, and the Indigenous Protected Areas system. In contrast with the Saami experience, she noted that many Indigenous peoples now have land, but no sustainable financing mechanism to manage it or to support cultural heritage and languages. She highlighted Traditional Use of Marine Resource Agreements in the Great Barrier Reef Park and the use of community protocols in the Northern Territories as examples of ways to overcome the great differences between local knowledge and Western science conservation-focused knowledge and different values and motivations therein. She underscored the importance of land and resource rights in addition to cultural rights as the legal foundation for supporting Indigenous peoples’ ways of life.

Holly Shrumm (Natural Justice) gave the closing presentation, providing an overview of a forthcoming volume of the CBD Technical Series on recognizing and supporting ICCAs as well as of the second phase of a global legal review on provisions that support or hinder ICCAs at the national, regional, and international levels. This follows from the first phase review, which can be downloaded here.