One week after having written the last exams for accomplishing the Master of Law in Switzerland, I came to Kenya for a fellowship with Natural Justice. With my legal background, I believe in the written text of the law and its enforceability. But, the three months in Kenya have taught me about other perspectives. Not everything is black and white like the paper and ink with which the laws are written down. The complexity of cases on the ground and the paths to tackle them are numerous.

In pursuit of social and environmental justice, the lawyers from Natural Justice are using the law to support communities to participate in decisions that affect their land, culture, and environment. This sounds wonderful, but what does this mission entail? What are the challenges the local lawyers are facing? I have had the chance to look over the shoulder of these top lawyers and get an insight into their daily work.

The cases Natural Justice is working on are numerous and every case has its challenges. It was very fascinating to learn about the different strategies of using the law to defend the voices of the local communities, with litigation as a last resort.

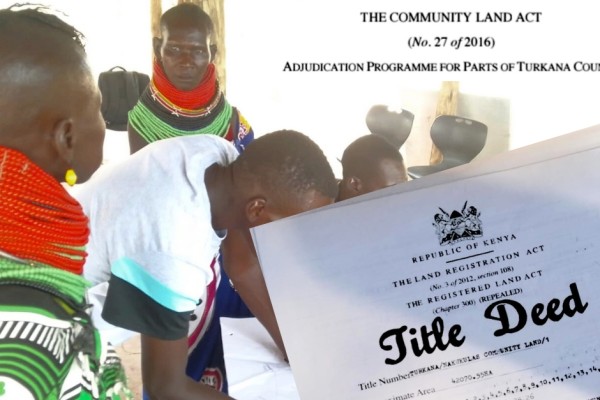

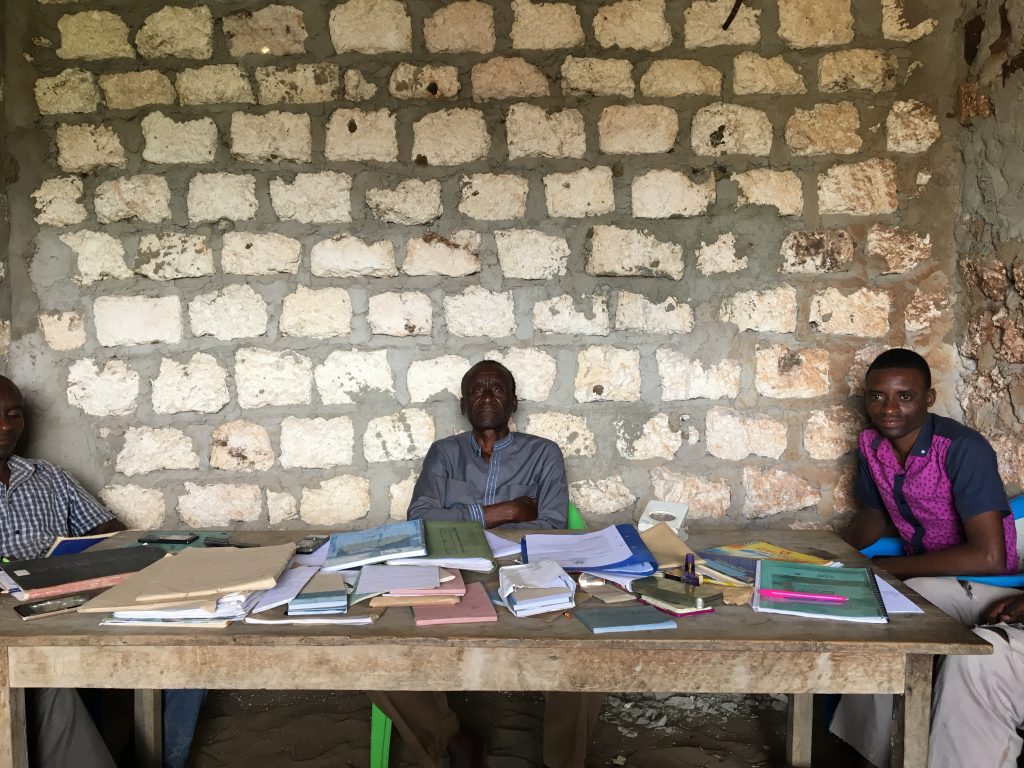

How do you make sure in a sustainable way that the rights of marginalized communities are respected? The keyword is legal empowerment! Only if people understand their rights and how to claim them, they can sustainably influence the respect of the law. To that end, Natural Justice established the position of the Community Environmental Legal Officer (CELO).

These paralegals are the interface between the local communities and the Natural Justice headquarter in Nairobi. The main office in Nairobi is where the research and the strategy-making take place. Just like the city of Nairobi, the Natural Justice Nairobi Hub is a place where people are walking and thinking fast – an inspiring place, full of life.

I’ve spent most of my time as a fellow at the Nairobi office where I felt welcomed and at home. Every now and then you find new guests from partner organizations, donors or colleagues from other Natural Justice offices sitting with us at the lunch table, discussing and joking.

But I also have had the pleasure to experience the work of the CELOs on the coast of Malindi- and Lamu Counties.

Natural Justice supports the local communities in defending their interests and informs them about the institutions and authorities to link with. However, it is always the communities expressing what they want, writing letters to the authorities and taking the next steps. The communities put a lot of effort into the process and leave their fishing activity, their farming aside, for the meetings with Natural Justice. Thanks to this empowerment they learn inter alia how to demand information based on the Access to Information Act that gives life to Article 35 of the Constitution.

In order to support the communities, the CELOs are in contact with the communities and meet up with them regularly despite some of them living in remote areas. What I found interesting and practical is that the CELOs are recruited from the community so they know the local languages and customs. In order to build trust, they need to be understood as one of them. Therefore, they use the cheapest means of transportation – no show off with big cars.

It’s only when the communities understand that you are actually on their side, that they will open up and you can reliably work together. As Martin Luther King said: “We’ve got to understand people, first, and then analyze their problems.”

This is how we ended up having a Tuktuk ride for one and a half hours to visit the community affected by the activities of the salt mining industry. On the way, it rained heavily and as we were about to leave the main road to visit the site, we were told that there is no way of accessing the site because of the muddy access road.

We learnt the only option we had was to drive another one and a half hour back to Malindi, soaked in water and the Tuktuk leaking from all possible and impossible sides. It’s during the rainy season that you learn the practical skill of how to choose the perfect Tuktuk.

Sometimes you have more luck with the weather on field visits. Like the time when we went to visit the Kwani farmers in Lamu County, which are still waiting to receive indemnification for their land that has been acquired for the planned Coal Plant. For this field visit, we had proper cars which is good because we needed to drive off-road for quite a while. We drove on the LAPSSET corridor road, until we turned on a smaller road, passing the water tower and then got off-road.

We passed a water tank in the middle of the fields indicating CSR. Our guide – a local paralegal with Natural Justice – explained that CSR stands for Corporate Social Responsibility and that the tank had a hole in it from the very beginning and was therefore never used…

This doesn’t leave me with a lot of hope for the other development projects of the LAPSSET corridor.

The weather needs to be good when visiting these farmers because we meet under a tree out in the cashew fields. After the explanation of the new strategy to receive indemnification, the farmers speak up about their concerns. Lastly, one farmer spoke up with this beautiful metaphor for the land grabbing that stuck with me:

“They came by night without even knocking at the door and made our daughter pregnant and then sneaked away. Though, in our culture, if you are interested in our daughter, we first sit together and talk about your intentions. But now that they have impregnated our daughter they are coming back and want to marry her and throwing the dowery at us.”

However, I must admit, during the meetings with the local communities, I could not understand much with my very limited Kiswahili. Therefore, I observed the people, how they talk, who talks and analyzed reactions. I noticed the meeting is only finished once everybody who wanted to speak spoke up. I also noticed the respect between people is crucial. Every meeting starts with a prayer from the eldest, followed by the introduction of the people present and ends with prayer again to let everybody leave in peace.

At Lake Baringo, I had the honor to attend a traditional celebration of the Endorois community. They were launching their community protocol, putting on paper a guide and negotiation tool ensuring legally sound procedures for external stakeholders wanting to interact with the community. As we were waiting for the governor to start the celebration, we had time to visit their Cultural Center and dive into their culture and their lands. As the governor arrived the traditional dancers welcomed him with song and dance marking the beginning of the ceremony for the launch of a new era for this community.

As romantic as this sounds, I don’t want to leave you with a glorified impression of Kenya.

I have also learned about corruption in the system. The frustration that comes after learning that a case you’ve been working on has just collapsed because some of your clients have been compromised, undermining all the time and skill invested. The government bureaucracy that made my colleagues sacrifice working days – needlessly waiting in front of the offices to follow-up with the authorities and insist on getting responses to their letters. I saw how successful advancements in front of the Environmental Tribunal are appealed and strategic games are played in order to weaken opposition against the government’s position.

During my fellowship, I not only learned a lot about legal empowerment at a national level but also had the chance to get involved in the preparatory session for a meeting of the Convention on Biological Diversity about the new global biodiversity framework. Natural Justice organized the preparatory meeting for representatives of local communities from across Africa – including Kenya – gathering their views and preparing them for international negotiations.

It confirmed to me the importance of the bottom-up approach. Actions on the ground ensure a successful implementation of a global framework. The people at the grass-root level depend on and care for their environment and are, therefore, likely to use it in a sustainable manner. Empower them, give them a stake and nature will blossom again.

With these excerpts of reflection, my fellowship with Natural Justice comes to an end. I have had a unique chance to dive deep into the culture and politics of Kenya. The lessons learned, the people I have met and the conversations I have enjoyed are countless. This fellowship leaves its traces not only on my curriculum, but also on my life experience.

I only have one more thing to say: Asante sana!