In the face of climate change, Indigenous peoples and local communities can be portrayed as victims of the crisis. However, these communities are not passive recipients of climate impacts; they possess a hidden asset that is invaluable for adaptation and resilience: their traditional and collectively held knowledge.

This knowledge is crucial for community-based adaptation and mitigation actions, yet it is often excluded from global decision-making and regulatory frameworks, ultimately weakening the resilience of these communities.

Natural Justice is committed to working with Kenya’s Indigenous communities to ensure their voices and knowledge are included in climate-related decision-making processes. The findings of our ongoing studies are instrumental in advocating for policies that are equitable, socially just, and environmentally sound. We visited three areas to understand community thinking around ways of adapting to climate impacts.

Lamu farmers forced to adapt

In Lamu, famed for its beautiful beaches and scenic views, farmers are navigating the intersection of age-old practices and modern advancements to enhance their crop yields.

Mohammed Rajab, Secretary of the Kililana Farmers Organisation, emphasizes the potential of traditional farming methods combined with modern fertilizers to improve productivity.

“Traditional farming methods and modern fertilizers help improve yields,” says Mohammed Rajab, Kililana Farmers Organisation Secretary. “Land should be farmed collectively, and fertilizers can assist in achieving better results.”

This approach underscores the community’s understanding that, while collective farming has long been a cornerstone of their agricultural success, the integration of modern tools like fertilizers is becoming increasingly necessary.

Ahmed Kihobe, a Kililana farmer, reflects on the past: “Early on, boats from the Middle East would come to buy our products. We farmed cashew nuts using Indigenous knowledge. We aim for pesticide-free food, but climate change forces us to adapt.” Like Mohammed, Ahmed’s words capture the resilience and adaptability of the Lamu community in the face of changing climatic conditions and their willingness to adopt new measures for resilience.

“Climate change affects our gardens and forest food sources,” explains Hadija Gurba of the Aweer community. “Women, especially pregnant ones, suffer the most. Erratic weather changes hinder our reliance on traditional knowledge.” Hadija’s testimony highlights the disproportionate impact of climate change on women. Climate change is forcing women to move out of their comfort zones and adapt their knowledge to new conditions.

However, these is one thing that threatens traditional knowledge: development.

“Winds have changed, affecting the number of fish,” says Somo M Somo, Chairperson of Save Lamu. “Progressions like roads impact our environment. Our grandparents could smell fish and rain, skills now being lost.”

His words underscore the urgent need to preserve traditional knowledge that his grandparents and their grandparents would have used in the past. He also shows that infrastructure development and modernity can take people further away from their traditional knowledge, creating both physical and social barriers to its retainment.

.

The Sengwer People: Custodians of the Forest

For the Sengwer people, who no longer have access to their traditional forests, the loss of resource access is eroding their livelihoods and disconnecting them from the opportunities to sustain their traditional knowledge.

“Women do not have proper places to stay, and the government has taken money for carbon credits,” says Albina Cheboi of the Sengwer community. “We no longer use medicinal plants, affecting our way of life and cultural practices.”

Albina’s concerns highlight the exclusion of Indigenous women from conservation efforts and the loss of traditional knowledge. In this case specifically, it shows the danger of solutions proposed by multinationals, such as buying up forest resources for carbon credit projects, and then excluding those that live there.

“We are Indigenous people living in the forest,” says Elias Kimayo. “Our community is not recognized by the government as Indigenous, though we are custodians of the forests.” Elias’s words echo the need for recognition and inclusion of Indigenous communities in environmental conservation dialogues. While international and national protection exists for Indigenous people, this is not respected by governments across Africa.

Elias describes their sustainable forest management: “We have divided the forest into three: areas for traditional practices, living spaces, and untouched areas. This sustainable approach respects our environment.” This reflects the Sengwer’s deep understanding and respect for their natural surroundings. It also recognises the role of Indigenous people as custodians – the protectors of the forest.

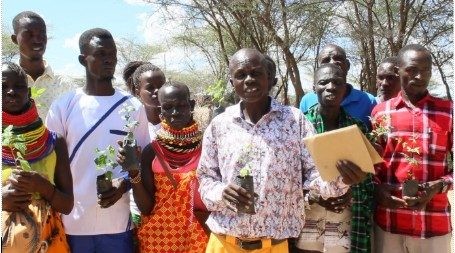

The Turkana People: Adapting Traditional Ways

In the arid and rugged landscape of Turkana, traditional practices are being challenged by the harsh realities of climate change and modernization. Marwes Ogirwe, a respected Turkana elder, reflects on the profound changes his community faces.

“Climate change has brought many changes,” says Marwes Ogirwe. “We gathered to pray for rain, and our livestock thrived. Now, resources are scarce, affecting our family structures.” Marwes’s reflections highlight the challenges faced by the Turkana in maintaining traditional practices amid climate disruptions.

The young are not spared either, as they are forced to embrace the evolving dynamics within the community as they adapt to new realities. “Youth today face many changes,” says Evans Echwa, a young person in Turkana. “Young men now stay at home, and traditional grooming is replaced by modern trends. While education is rising, we’ve lost the old medicine men who predicted the rain.”

Conclusion

Integrating traditional knowledge into climate resilience strategies is vital for empowering Kenya’s Indigenous communities. However, there are challenges to how traditional knowledge is retained and passed on. More needs to be done to expose youth to traditional knowledge, but also to offer adaptations that can complement the existing and ever-changing traditional knowledge that communities hold. It is built over thousands of years and will continue to be built upon into the future. Climate change merely offers a more accelerated challenge.

By involving Indigenous peoples in policymaking, we can create more effective and just solutions to climate change. The voices from Lamu, the Sengwer, and Turkana underscore the importance of preserving and integrating traditional knowledge for the global fight against climate change. These communities hold the key to a more sustainable future, reminding us that resilience lies in the wisdom of the past.