Natural Justice attended the United Nation’s First Substantive Session dubbed “Towards a Global Pact for the Environment” between 14-18 January 2018 in Nairobi. We were there to take part in deliberations on, among other matters, the Secretary General’s report titled ‘Gaps in International Environmental Law and Environment Related Instruments: Towards a Global Pact for the Environment’. The report was prepared pursuant to Resolution 72/277 of the General Assembly for consideration by an ad hoc open-ended working group established with a view to, “identify and assess possible gaps in international environmental law and possible options to address possible gaps in these international environmental laws and environment related instruments”.

But where were the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities when such weighty matters that affect them were being discussed?

It was our wish that the meeting would provide impetus for the preparation of a roadmap for a more coordinated and harmonized way of implementing international environmental law and other environment-related instruments to create a win-win situation for the environment, the planet and its inhabitants. This we thought was critical and timely due to the urgency demonstrated by the Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming wherein the authors warned that, “Global warming is likely to reach 1.5oc between 2030 and 2052 if it continues at the current rate”. Even more alarming is knowing that 2030 is the near future, and the urgency with which all actors and agencies, including communities, must engage concerted actions cannot be overemphasized.

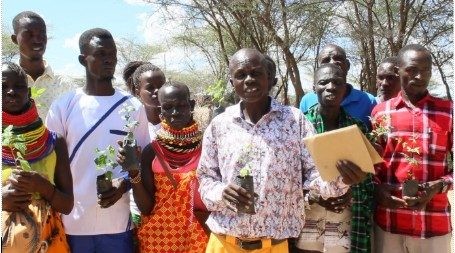

Few NGOs attended the meeting and of concern was the absence of other Indigenous Peoples and Local Community representative groups. Natural Justice was particularly keen on the participation of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities due to their close relationship with land, environment and natural resources. Policies, laws and agreements reached at the international level impact them, their cultures and traditions in the long term and it is important that they participate in these types of fora to demonstrate their role in the environment, land and natural resource governance regime.

The report concentrates on international environmental law and environment-related instruments, but in our view, there is need for in-depth consideration of the impact of these laws and instruments on Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. However, there could have been several other reasons for non-attendance, such as lack of accreditation or funding. It was clarified by the UN Civil Society Unit that, of the 64 approved applications, about 20 NGOs attended, meaning there were other reasons for failure to attend and this is perhaps a conversation that civil society ought to have with a view to resolving the challenges in the long term, considering that Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities are key actors within any governance system, as they are impacted by laws and policies that are put in place. Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities also have capacity to contribute to the social and economic well being of the society.

Towards this end, in the Statement that Natural Justice helped prepare on behalf of NGOs at the meeting, it implored the Working Group to include, among other matters, “new and emerging principles and concepts such as just transition, sustainable production and consumption, rights of future generations and indigenous people and local communities”, in the proposed Pact.

It is critically important that Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities be engaged in any discussions surrounding management and governance of land and natural resources because they live in the very ecosystems that are managed and governed by a plethora of laws and instruments, some of which are still under discussion. In the case of Indigenous Peoples, Principle 1 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) provides that they are entitled to the right to full enjoyment, as a collective or as individuals, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms consistent with several UN instruments. Some of these instruments, such the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration on of Human Rights, are key references in the Secretary General’s Report and this shows the interaction and interconnectedness between various instruments and the need for broader perspectives and inclusiveness in discussions on the Global Pact.

Rockstrom et al reveals that, ‘’interactions among planetary boundaries may shift the safe level of one or several boundaries’’. This, in our view, ought to be the concern of all States, agencies and actors, including Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. Chapter six of the World Science Report (2013), presents a a doughnut-shaped framework that shows the interaction between social and planetary boundaries and the space within which all of humanity can thrive. According to Rockstrom et.al (2009), planetary boundaries are interdependent and transgressing one would most likely interfere with one or several others with resultant ripple effects. These planetary boundaries include: climate change, ocean acidification, stratospheric ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading, biogeo-chemical flows involving interference with phosphorus and nitrogen cycles and, global freshwater use, which form the foundation for new approaches to governance.

According to Rockstrom, humanity has already transgressed three boundaries (climate change, the rate of biodiversity loss and the rate of interference with the nitrogen cycle). Will Stephen et. al warns that, “if the threshold is crossed, the resulting trajectory would likely cause serious disruptions to ecosystems, society and economies”. The authors go on to state that, “collective human action is required to steer the Earth system away from potential threshold and stabilize it”, action which, “entails stewardship of the biosphere, climate and societies and could include de-carbonization of the global economy, enhancement of biosphere carbon sinks, behavioral changes, technological innovations, new governance arrangements and transformed social values”.

One of the planetary boundaries on biodiversity loss could be checked through extensive engagement and involvement of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities as they have the capacity to contribute to increasing biodiversity, health and ecosystems, which would in turn support other ecosystems. This position is underscored by the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem services as discussed by P. A Harrison et. al.. More specifically, Stephen T. Garnett et. al show that “Indigenous Peoples manage or have tenure rights [over at least] a quarter of the world’s land surface”, “intersect about 40% of all terrestrial protected areas and ecologically intact landscapes…[and] that recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ rights to land, benefit sharing and institutions is essential to meeting local and global conservation goals”. It concludes that, “collaborative partnerships involving conservation practitioners, Indigenous Peoples and governments would yield significant benefits for conservation of ecologically valuable landscapes, ecosystems and genes for future generations”. This means that missing out on this critical aspect could cause the entire human race to lose out on potential benefits. Thus, the authors’ call for new governance arrangements is precisely what a Global Pact could achieve.

It is critically important that the States and agencies and actors engaging in discussions surrounding the Global Pact engage a broader view with these interactions in mind and ensure that they include principles that safeguard and include the rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

Towards this end, we encourage groups representing Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities be in attendance during the Second Substantive Session on the Global Pact on Environment scheduled to take place between 18-20 March 2019 at Nairobi.