There is a perception of lawyers as people who wear suits and hold heated debates in court rooms. But this narrow stereotype could not be more incongruent with the reality of the lawyers involved in human rights work. These lawyers spend long days in the field with communities, building relationships, trust and solidarity. They commit their life’s purpose to these relationships and cases – suffering painful personal outcomes when things don’t go as planned.

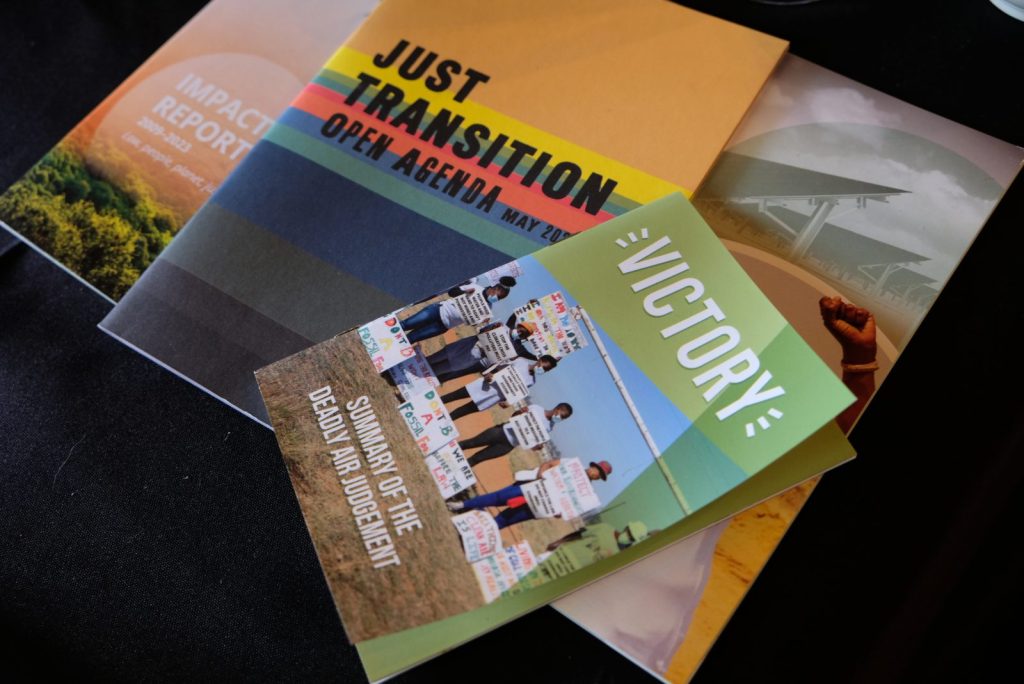

Human Rights work happens in a challenging environment – the dynamics of which was discussed during the Environmental Lawyers Collective Africa (ELCA) convening in Cape Town a few weeks ago. The convening brought together environmental, and public interest lawyers from various Southern African countries, to share their challenges and successes undertaking legal actions in their respective countries.

Community lawyers, human rights lawyers, activist lawyers, regardless of what you call them, they are working in environments that are professionally and personally challenging. However, they are compelled by a desire for justice. And they know that victories matter.

The victories matter because we are living in a world constantly in crisis – and things are going to get worse. Many years ago, scientists told us to keep global heating to below 1.5C – but last year we briefly passed that mark, and the implications are clearly documented and truly frightening. We know the power of law (and of knowledge), and so the mission of an environmental lawyer is to not only bring the law to people, but shape the law in order to deliver intergenerational justice – and ensure a world that our children can survive in.

With our children’s future in our hands, there is a sense of urgency. And yet the actions of polluting companies and corrupt governments haunt the courtrooms of the world. The law is disregarded, ignored or, in the worst cases, weaponised. Based on discussions over the four days of the convening, I aim to showcase the challenges – personal, professional and within the law – that frustrate the work of human rights lawyers.

Working with communities

Community lawyering involves showing up in community spaces. Community lawyers cannot impose their own principles – they must work within a community based on its social dynamics. They need to be invited into that community. They need to understand customs and hierarchy. This can mean stepping back from their own ethos at times. However, if a lawyer cannot gain community trust, there will be no progress.

This also applies to the advice that is provided. Contrary to what government or companies will tell you, community lawyers are not there to impose their beliefs – for example, by saying that “mining is wrong”. They have a duty to provide the skills and knowledge that will help a community make decisions for themselves. Communities can negotiate or proceed, but it needs to be their decision. This can sometimes mean that a lawyer must step away from their own subjective desires – whether to reduce carbon emissions, protect land or stop mining from happening.

Of course, it is also important to recognise that using the word “community” can be complicated. A lawyer must be satisfied that the structure they are working with actually has the mandate of the community. A lawyer must be careful that a concerned group can arise within communities because they, for example, are concerned about pollution or land grabbing, but they may not represent the interests of the community.

Divisions and disagreements

How a lawyer approaches a situation and the strategy they use to support a community to use the law – whether through negotiations, mediation, empowerment or litigation – can have ramifications. Litigation can create divisions in communities. Certain “clients” within the community can gain power by being part of court cases or community actions, and suspicions can arise within the community.

Divisions and disagreements due to interference from outside actors have serious implications. There have been threats, assaults and even assassinations within communities – sometimes from neighbours or family members that disagree with a side. In places like KwaZulu Natal, assassinations and attempted assassinations are common, not just because of community tensions, but because of political and economic ambitions.

As one lawyer put it, “There is always risk in this work… As lawyers, you question whether you have created this…”

It has been long known that these divisions are sometimes manufactured by the company or government when they are interested in the land or resources that the community has access to. Payments are made to leadership, or bribes are offered. Sometimes it is simply that false promises of jobs and services are made. These divisions can hinder progress on an issue and of course, make working in that space frustrating (and sometimes dangerous).

Breakdowns in relationship

Emotional burn-out amongst community lawyers is real and frightening. I have seen it happen to many lawyers, especially those facing personal threats. Community lawyers have a certain persona and identity wrapped up in their work, and maintain a deep commitment to the work despite the odds. Emotional burnout is something that community lawyers must protect themselves from. Other clients will also need them and often the non-profit they work for has other demands (fundraising, reporting, planning etc).

When issues between a lawyer and the community unfold, a community lawyer must remain curious. Sometimes, yes, there could be a group that has nefarious intentions, or it can simply be a misunderstanding. It could also be the other side that is interfering. A lawyer must set aside their personal feelings – which can be extremely heartsore.

One lawyer at the convening put it succinctly: “I need to create a buffer between me and the community…there is a certain element of myself that I need to leave behind in order to protect myself from emotional burnout. How can you do this?”

The question posed to the room created a seriousness, and even desperation – because for many, this is their most burning issue. The best advice given was to acknowledge that we are human, treat “heartbreak” as heartbreak and maintain a life and healthy relationships outside of work. And of course, don’t wrap up your whole identity in the work.

Personal and professional threats

When it comes to personal and professional threats, one case study comes to mind: The SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) suit against activists and lawyers in South Africa instituted by the Australian mining company, Minerals Commodities Limited (MRC), who had plans to mine the dunes of Xolobeni on the Wild Coast of South Africa. The case involved a defamation suit against six activists, including two lawyers.

When the case arrived at the doors of the Constitutional Court, the Court did find it was an abuse of process by MCR. MCR, being in the firing line, had to go back to the High Court. It was decided that settlement was the best option for everyone, as the activists and lawyers were exhausted and burned out. Seven years had passed since the case began. The process was hugely stressful and took a lot of time and attention away from the work the activists and lawyers were doing. Of course, this is why companies use SLAPPs.

SLAPPs are just one of the threats against lawyers all over the world. There is a rising tide of proposed legislation that will close down civil society organisations by restricting funding (no more “foreign funding”) or by accusing activists and lawyers of terrorism. Laws that require strict registration of organisations, as well as staff, can allow the government to de-register the organisation at any time. One example of this is the “counterterrorism” law proposed in Mozambique, which could see lawyers go to jail for spreading so-called “false information” – or rather information that the government does not want people to know.

Another threat comes from the “capturing” of the judiciary, where judges favour government in their judgments, because to disagree would mean career-suicide. This results in human rights cases losing in court.

In many countries, going to court could means that cost orders are made against the organisation or your community-client. This can be financially crippling for an NGO or person, and makes going to court risky.

In South Africa, public interest lawyers have been protected by the “biowatch principle”, but lately courts have been regressive in their application of this important principle. One of these cases went to the Constitutional Court, brought by Natural Justice and Greenpeace Africa. The Court upheld the cost order against these organisations, which could have a chilling effect on future court cases.

Fighting the narrative

Civil society organisations have been called CIA funded, anti-development, “Apartheid and colonialism of a special type”. While coming from only one or two people at the top, the distrust of the intentions of human rights lawyers has infiltrated into the communities they serve. This is dangerous territory, as it is likely to fuel the tensions and divisions within communities.

Particularly dangerous is the anti-development rhetoric. This is the belief that non-profit organisations do not want a community to “develop”- i.e. have new infrastructure, services, or job creation opportunities.

Of course, this is not true. Community lawyers want “development” but development that involves the community in decision-making, does not heavily impact their environment, livelihoods or culture, and upholds the rights of the community. This is only restrictive of development in the context and history of development. If all of these factors had been considered in past decisions, we wouldn’t have a world in crisis. In Africa particularly, the wealth of natural resources has been plundered by external interests, and people on the ground are still living in poverty, and often disconnected from their livelihoods, culture and connection to nature.

There are other narratives that community lawyers are faced with – many related to the energy and agricultural sectors (which is where the climate crisis begins). These are the “false solutions” or misinformation that is offered by industries and governments in order to remain in powerful positions, reaping profits and continuing to contribute to the crises of racism, poverty and inequality.

There is a long list of these narratives which all feed into the beliefs around “development”, as it is in the traditional sense. Understanding each of them in great depth, and considering all the arguments around them, means that community lawyers become experts on issues of energy grids, gas, nuclear, lifecycles, carbon emissions, biodiversity and culture (and so much more). While it can be exciting, it means a lot of time is spent on research, engaging experts and counteracting the narratives.

Solidarity-building across Africa

It cannot be over-stated: we are in a crisis. We cannot afford to build more fossil fuel projects, mine for oil and gas, or plunder our land and biodiversity. The work of human rights lawyers is crucial, and they require support, protection and resources to carry out their mandate successfully. As one speaker at the ELCA conference put it, “Lawyers have the best ability to bring activist, technological, scientific and policy spaces all together…this position is actually unique and privileged. Therefore, we as lawyers, have a duty to ensure that knowledge is being shared as much as possible.”

ELCA has been established to provide the support needed to be activists and lawyers. Only together, will we continue to build towards a climate just world for us and the children.