On 28 February 2023, a French court declared an appeal against a controversial oil and gas project in East Africa, largely owned by TotalEnergies, to be inadmissible. The dismissal of the case allows TotalEnergies to continue with the development of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) contrary to requests by those opposing this for any development to be halted until TotalEnergies had addressed human rights and environmental concerns. Sitting in summary proceedings, the Judicial Court of Paris did not assess the details of the claims brought by several NGOs but dismissed them based on various technicalities.

Six French and African civil society groups had called for the court to order the suspension of the Tilenga oil field development and EACOP, arguing that TotalEnergies had failed to comply with France’s “law on the duty of vigilance”. This novel legislation, passed in 2017, requires large French-based companies to draw up clear measures to prevent human rights violations and environmental harms whether through the activities of the company, its subsidiaries, sub-contractors, or suppliers with whom it has an established business relationship. Based on this, TotalEnergies developed a “vigilance roadmap which it claimed was compliant with its legal obligations. The plaintiffs said this was insufficient and warned that the enormous oil projects will cause widespread human rights abuses and irreversible environmental damage.

The French court dismissed the appeal on two main counts. Firstly, the court said that the claims raised before it were substantially different from those originally presented in 2019. Since then, TotalEnergies has published three subsequent vigilance plans. The court said the civil society organisations ought to have issued a fresh formal notice in relation to the company’s 2021 vigilance roadmap, rather than updating the old appeal.

Secondly, the court said that it was not within the court’s powers – sitting in summary proceedings regarding urgent applications – to conduct the kind of thorough analysis of the case that would be necessary to assess its merits. The court therefore neither validated the plaintiffs’ appeals nor vindicated TotalEnergies’ defence.

Silver linings

The plaintiffs have expressed deep disappointment at the ruling, especially following such a protracted court battle. They had hoped that the legal case in France would set a ground-breaking precedent and believed it had a greater chance of success than various legal cases filed in East Africa. They maintain that the development of 400 Tilenga oil wells and the construction of the 1,443km-long EACOP will negatively affect 100,000 people and cause environmental devastation.

While these civil society groups did not get the verdict they hoped for, all is not lost. For starters, the plaintiffs are considering appealing the verdict. Even if they do not, however, it is notable that the French court indicated that the plaintiffs’ claims could, in principle, be pursued before a trial judge with the jurisdiction to assess the claims in depth. Contrary to TotalEnergies’ argument that the plaintiffs lacked the legal standing to bring the case in the first place, this leaves the door open for similar organisations to bring similar claims in the future.

This should be seen as an important milestone in and of itself, demonstrating the potential scope of application of France’s vigilance law. Though dismissed on technical grounds, the EACOP case highlighted companies’ increasing legal responsibilities to address human rights and environmental concerns in their operations – and not just as a matter of soft law but binding legal obligation. And, not just in relation to the company’s direct activities but those of its foreign subsidiaries.

Another notable aspect of the case is the decision by the plaintiffs to demand that Total take into account all the projected greenhouse gas emissions associated with the Tilenga and EACOP projects. That’s to say the calculations should include not just scope 1 and scope 2 emissions – i.e. those directly owned or controlled by the company – but also scope 3 emissions. This latter category encompasses the wide range of emissions up and down the value chain, such as those related to the maritime transportation of oil and from the eventual combustion of the oil extracted. Taking into account a project’s entire emissions output is an essential corrective legal measure to the much more limited manner in which emissions have been added up historically and an important protection against corporations’ well-evidenced greenwashing strategies.

Just the beginning

TotalEnergies may have breathed a sigh of relief at the recent French verdict. But, as it celebrates last year’s record net profits of $20.5 billion, the oil major may also have reasons to be concerned as it looks ahead. Calls for accountability are likely to grow as the effects of climate change are increasingly felt, especially among the local and Indigenous communities who bear the brunt of environmental impacts and human rights infringements while seeing little of the profits.

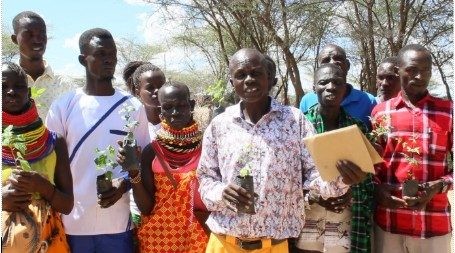

As the case against Tilenga and EACOP showed, this resistance may come increasingly through global solidarities forged between local communities, national civil society groups, and international NGOs. Despite the disappointment in Paris, the legal challenge against TotalEnergies could inspire similar cross-border coalitions to join forces and submit similar legal challenges based on duty of vigilance laws.

Such solidarities are particularly significant as reprisals against environmental and human rights defenders in much of the world grow. Amid this increasingly hostile backdrop, the potential for bringing legal actions against companies’ parent corporations in the likes of France (and hopefully other countries too) provides communities and activists with an alternative avenue to pursue claims that would be unlikely to succeed in partisan national or regional courts.

With Tilenga and EACOP scheduled to become operational in 2025, the plight of affected communities in East Africa is far from over. However, with the door still open to pursue legal claims in France – and with several other coalitions from around the world filing cases against big French corporations under the same duty of vigilance law in recent years – the same is true of potentially game-changing calls for global corporate accountability.

Litigation at the East African Court of Justice

Separately, a case challenging the construction of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, instituted by a coalition of African civil society organisations, including Natural Justice, is scheduled to be heard on 5 April 2023 in the East African Court of Justice. The governments of Uganda and Tanzania, as well as the Secretary General of the East African Community, against whom the case is filed, challenge the jurisdiction of the court to hear the case. This is the first matter to be considered and the parties in the case will present their arguments on the question of the court’s jurisdiction on 5 April. This will need to be considered and addressed before the court establishes whether it can hear the case on its merits or not.

Despite filing the case together with an application for a temporary injunction in November 2020, the wheels of justice have moved incredibly slowly, with devastating consequences for communities who are bearing the heavy project impacts even before it breaks ground. The project has also had consequences for activists in Uganda, who are already experiences reprisals. As the latest IPCC Synthesis report warns of climate impacts likely to be more severe than anticipated, one hopes the court will not only deliver justice but do it expeditiously, recognising the urgency the climate crises demands.

(An earlier version of this article was published by African Arguments on 14 March 2023)