Background

Located at the center of Kenya, Isiolo town stands as a platform of immense possibilities in the Northern region. The town has been earmarked as a developmental center, with the Kenyan government recently building a new international airport and now planning a resort city. These activities and aspirations have made the town feel bigger than it actually is and though many are eyeing a new grandeur, simple and recurrent complaints on the local development processes are being ignored.

The growth of the town over the years reveals poor planning. The hitherto out of town slaughterhouse has been overtaken by the sprawling settlements. As one walks through the neighborhoods of Camp Odha, Camp Bule, Camp Garba, you cannot help but cover your nose to prevent the assault on your olfactory senses. This strong stench has not only lowered the property values in the area but has also made it hard for the residents to enjoy the comfort of their homes. I was informed by one resident that, “one cannot sit outside under these shades to enjoy a meal.” I had a glimpse of the poor state of the slaughterhouse, the open drains clogged by bowel waste, blood and meat on the floor, a pool of sewage waste in the nearby lagoon – the source of all the stench.

In my role as community environmental legal officer with Natural Justice, I spoke to Godana Molu one of the almost 1000 residents of the area and the coordinator of Vision of Hope, a community based organization (CBO), who explained the effects of the slaughterhouse on the neighborhood and all the past efforts, media coverages, protests and unanswered letters to different offices to bring the plight of the residents to the attention of the local and national government with little result.

A simple background check earlier in the year revealed a tome of media stories on the poor state of the slaughterhouse, and its recurrent impact on the residents. Isiolo being in the oft-marginalized northern Kenya has few community or professional lawyers taking up such environmental justice cases for affected citizens.

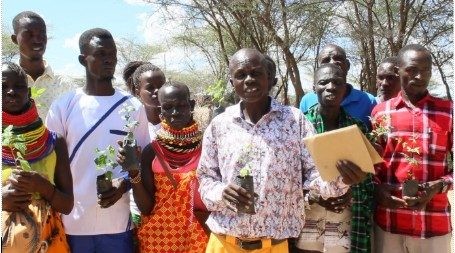

I began to support Vision of Hope to utilize some of the administrative mechanisms that exist to deal with the very issues raised by affected community members. Our endeavor here was to follow the more silent, sustained and legally established channels, shelving the cynicism borne by many others who had tried this previously and failed.

We first collectively looked at the relevant environmental and public health laws and compared these to the actions, or in-actions, of the slaughterhouse. The Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) requires that a project, such as the slaughterhouse, be granted an environmental license and have regular environmental audits. These should all be overseen by the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA).

It took a few access to information requests to NEMA to establish that the slaughterhouse did not have an environmental license and obviously had not been subjected to any audits to assess its environmental and social impacts. With this knowledge the community organization submitted a formal complaint to NEMA highlighting the clear legal violations of the slaughterhouse.

Community members, with the support of Natural Justice, also filed a written complaint with the Isiolo county public health office on the basis of the severe odor from the slaughterhouse, which we submitted was a public nuisance and thus a violation of section 118 of the Public Health Act. In the letter, we requested the Office to serve an abatement notice on the business requiring it to undertake measures to prevent future offensive smell. This letter invoked the Public Health Office’s mandate under section 116 of the Public Health Act to take “lawful, necessary and reasonably practical measures for maintaining its district at all times in clean and sanitary condition, and for preventing the occurrence therein of, or for remedying or causing to be remedied any nuisance”.

We did not receive a response to our initial request, however, on following up with the Director of Medical Services, we were given a verbal acknowledgement and promise to resolve the nuisance. At about the same time, NEMA also acknowledged our complaints and indicated it would follow up on the issue. Over the next two months we kept lobbying the same offices with phone calls and letters, not allowing any promise to pass without our follow ups.

In July, more than 7 months after we began our initial inquiries, a public health officer and his field staff attended the slaughterhouse, where they saw firsthand the deplorable state of operations and clear legal violations. A closure notice was provided to the slaughterhouse five days later. This all came barely a week before Kenya’s general election and amidst fears of ruffling the feathers of the meat loving nomadic (or pastoralist) population and a class of influence bearing bureaucrats. Seen in this light, the closure of the slaughterhouse for its legal violations is quite monumental.

Though many remain skeptical of our government’s ability or interest to solve community problems and the slaughterhouses reopening has dented the positive atmosphere that existed within the community, this partial intervention has provided some hope that these regulatory institutions can be used to hold the government and businesses accountable.

At a time of elections in Kenya, the slaughterhouse issue fits into a larger national struggle – presidential aspirants and lone pedestrians are learning to believe in and invoking a new constitution to hold established institutions to account. It’s an important reminder of the role such institutions must play in a functioning democracy.

Dalle Abraham is a Natural Justice community environmental legal officer working in Marsabit and Isiolo Counties.