Who has the monopoly in the move towards a Just Energy Transition? Who benefits most and who gets left behind?

Community representatives from various corners of the country considered some of these crucial issues at the Just Energy Transition and Extractives Indaba heldin Rustenburg in the North West Province of South Africa in October 2025.

These considerations ultimately highlighted two key elements – can Africa transition without repeating old extractive models? And can we unite communities to build an impactful movement towards a Just Energy Transition future?

Driving along the N4 highway from Gauteng to North West Province in South Africa, you will pass the Magaliesberg and Witwatersberg mountain ranges to find the popular Hartebeespoort Dam. There is a holiday feeling in the air. Soon after, the landscape changes dramatically, becoming greyer and starker as you’ll pass mine-after-mine on one side of the highway. While the North West is known for iconic tourist attractions like the glitzy Sun City resort and the abundant biodiversity of Pilanesberg National Park, the area is also rich in mineral resources and heavily reliant on extractive industries. The province’s mining industry is believed to generate over 50% of its GDP where gold, uranium, platinum, and diamonds are commonly mined. For this reason, the region had been strategically chosen to host the African Activist for Climate Justice’s Just Energy Transition and Extractives Indaba.

What is the Just Energy Transition and Extractives Indaba?

Extractive-led economies often reproduce environmental injustices, dispossession, and exploitation. On the frontlines, trying to prevent the exploitation of vulnerable communities, you’ll find groups of grassroots movements and community-based organizations, women’s rights groups and youth networks, civil society and climate justice organizations. These were among the 63 activists who gathered in Rustenberg to deliberate on extractives, energy futures, and climate justice – a gathering that included an eye-opening trip to a mining community.

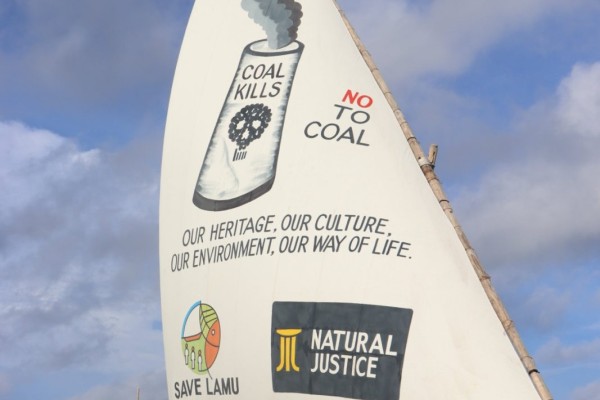

The indaba was a joint event hosted by consortium Partners Oxfam South Africa, Natural Justice, PACJA, and FEMNET, under the Africa Activist Climate Justice (AACJ) banner.

Why were we talking about JET?

Guest speaker, Dr Janet Munakamwe, told participants that we cannot talk about JET without talking about climate change.

“Transitioning from where? For who? What are the alternatives? Words matter: Just Energy Transition presupposes that we are all on the same footing and will then ‘transition’ together. The point of departure is noting where are we?”

She highlighted that transitioning to clean, resilient and equitable energy systems is heavily influenced by conversations usually done at international level, with governments and companies entering agreements, without community voices or grassroots realities being considered.

But first! Understanding the struggles to stand united

Indaba participants arrived from coastal communities, mining-affected and farming communities further inland – who face a variety of daily struggles. Unregulated small-scale mining practices, oil and gas related issues, climate change and its effects on fishing catches and livelihoods, unemployment, gender-based violence, teenage pregnancies, gangsterism are some of the many challenges that they confront. It was clear that all the participants were united against the exploitation of resources that has negative impacts on their environments and ultimately their lives.

Critical discussions centred on the perceptions and misconceptions around miners, mining communities and practices and the work of the National Association of Artisanal Miners (NAAM). NAAM has been championing a comprehensive legal framework that considers the voices and interests of Artisanal and Small-scale Miners (ASM).

Key points highlighted included the cultural significance of ASMs, which has been passed on from generations and is part of people’s livelihoods. It was also highlighted that many people are not familiar with the differences between “Zamazamas” (illegal artisanal miners) and ASMs, which causes confusion and misconceptions.

They spoke about how abandoned mines leave mine workers in a devastating way; how communities are not being consulted on mining projects; how transferals of the mine from one developer to another can have a disruption element or impacts on the mine host communities; and how miners often have no access to power (electricity), while neighboring communities do. These issues highlighted why the move towards JET would need to ensure better alternatives.

Millicent Shungube deputy chairperson of NAAM said it was a big step to attend events like the indaba. She said the association aims to eliminate the word Zamazama and replace it with Abavukuzi (which means “to strive”) to change the negative perceptions.

“For us pushing the formalisation and regulation – it’s important for this kind of support. These are people who trying to make a living. We are grateful for the solidarity and the platform. We’re waiting for the policy to be implemented.”

A site visit to a local mining community – surrounded by formal and informal mines brought the issues to life. Seeing the conditions under which miners live and hearing the difficulties surrounding the regulations of the informal mining sector were shocking for many of the participants.

Collin Munakamwe from the African Diaspora Workers Network (ADWN) had mixed feelings.

“It was hard to see how some people out there actually sacrifice. As we were moving through the mines and on the other side saw the townhouses – and the shacks and as you move from the mines you see beautiful houses. It was a stark contrast – a juxtaposition – to see a huge gap in how people live.”

Can Africa transition without repeating old extractive models?

Africa has contributed the least to climate change, yet it faces the harshest impacts like inequality, poverty and increasing vulnerability for marginalized communities.

The indaba therefore looked at how to strengthen collective advocacy that could influence climate policies and how do we foster alliances among community-based grassroots movements, civil society and policymakers.

The indaba discussions were a clear reminder that the duty to bring about socio-economic development that is not harmful to the environment and the wellbeing of people is a constitutional mandate vested on the government, particularly local government. However, this duty has been negated by the local government because of the presence of mines in communities.

Reparations, Redistribution and Responsibility

Liveson Manguwo Senior Programmes Manager (Programme quality and effectiveness) from Oxfam South Africa noted that, while the energy, infrastructure and mining sectors continue to exacerbate the fossil fuel and extractives industries, these industries are important for communities and we will need to re-think how we sustain, redistribute and redress.

He said: “This requires us to be more radical in our asking: it must be fair, equitable and just. Let’s make sure that communities are centered and involved in beneficiation, climate finance, and decision-making.”

Amelia Heyns, Programme Manager for the Standing with Communities Programme at Natural Justice added that JET describes where we are going, and how we get there and JET principles indicate that we need to move away from the current state.

“We know that we cannot keep going on like this, knowing SA’s reliance on fossil fuel energy. Understanding the triple crisis of unemployment, inequality, and poverty while at the same time, we understand our environmental boundaries (tipping points) and social impacts of the JETs.”

She said that understanding the urgency of the transition to renewable energy is important.

“We cannot create a future that is worse than what it used to look like. Everyone must have access to energy that is also affordable.”

Heyns said that JET will need to respect communites’ right to give consent governance structures which include traditional authorities, community structures and meaningful, inclusive and transparent action.

“Communities have a right to actively engage the state in decision-making, how to ensure that mines account for a just future. Good governance requires communities holding government accountable. We need to see that we get there.”