Tucked along Kenya’s coastal belt in Kilifi County, the Uyombo community lives between the sacred Kaya forests and the turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean. This is a place where livelihoods are deeply tied to land and sea, where fishing, farming, and tourism converge to support many family generations. The white sandy beaches they steward are not just postcard-perfect—they are also economic engines, contributing significantly to Kenya’s tourism industry, which accounts for an estimated 8.8% of the country’s GDP.

But today, Uyombo faces a threat unlike any it has seen before: a proposed nuclear power plant.

Without warning or informed engagement, the quiet village of Uyombo found itself on the list of possible sites for Kenya’s first nuclear facility. This decision was made far from the community, in government offices and international boardrooms. Just recently, a delegation of high-level officials—including members of Parliament and the Senate Committee on Energy—travelled to Vienna to engage with the International Atomic Energy Agency. Meanwhile, the people of Uyombo are left with more questions than answers.

They have already spoken clearly and repeatedly. They do not want a nuclear power plant on their land. They do not consent to becoming a testing ground for a technology they were never consulted about. They reject the paternalistic assumption that lack of formal education equates to lack of wisdom. What they lack in technical jargon, they make up for in lived experience, environmental stewardship, and historical memory. Many speak of disasters like Fukushima in 2011, or Chernobyl before that, not as distant events, but as cautionary tales of what can happen when people are ignored.

And they ask: If disaster strikes, is the Kenyan government prepared?

Rising in Resistance

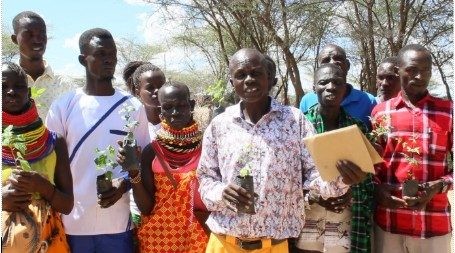

The Uyombo community is not remaining silent. With the support of Natural Justice and other civil society allies, they are asserting their constitutional rights:

- The right to access information (Article 35)

- The right to public participation (Article 10)

- The right to a clean and healthy environment (Article 42)

Through community assemblies, legal empowerment forums, and formal petitions, Uyombo has delivered a powerful message:

“We will not be sacrificed in the name of development. We are not guinea pigs for nuclear experimentation.”

Their position is grounded in both principle and lived realities:

What’s at Stake?

From the very beginning, the proposed nuclear energy project in Kenya has been marked by deep legal and procedural violations. Find the submission and fact sheet that Natural Justice prepared for the Departmental Committee on Environment and Natural Resources of the National Assembly.

The Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA)—a process meant to safeguard the public interest—was fundamentally flawed. It excluded the voices of nuclear safety experts and sidestepped meaningful consultation with the very communities whose lives and livelihoods are on the line. It failed to consider viable, safer alternatives such as wind or geothermal power—resources Kenya is abundantly blessed with.

This oversight is more than just a bureaucratic lapse; it is an act of environmental injustice. Kenya currently has no robust legal framework or institutional infrastructure to manage radioactive waste, respond to nuclear accidents, or track the long-term health consequences of exposure. For communities like Uyombo, these gaps are not abstract—they are real, and they are terrifying. They recall the painful lessons of the past: the lead poisoning in Owino Uhuru and the oil spill in Thange, where justice was slow or never came at all. There is little faith that things would be different this time.

More troubling still is that this risk is entirely unnecessary. Kenya is not facing an energy shortage. With an estimated renewable energy potential of over 33,000 megawatts—far exceeding the country’s projected demand—there is no rational basis for embracing a costly and dangerous nuclear path. The choice to pursue nuclear energy in the face of such abundance is not just ill-advised; it is irresponsible.

At its core, this project represents a violation of energy justice. It bypasses transparent, inclusive decision-making. It ignores the rights of present and future generations. It risks exacerbating social inequality, placing the greatest burdens on those with the least power. And perhaps most gravely, it silences the voices of communities who will bear the brunt of its consequences.

This is not the energy future Kenya needs. And it is not the justice our people deserve.

A Just Transition Begins With People

All over the world, countries are preparing for an energy transition and moving from the old to the new. Any energy transition must be just: rooted in community agency, accountable governance, and environmental sustainability. Development cannot be imposed. It must be negotiated. It must be grounded in law. And above all, it must respect the rights and wisdom of the people whose lives are at stake.

The struggle in Uyombo is about more than nuclear power. Although we must think about the immediate dangers of nuclear to people and the environment, this is more at stake. This struggle is a demand for transparency and a call for meaningful participation. It is a stand for climate and energy policies that centre people over profit.

As government representatives prepare to visit Uyombo for a “consultative meeting,” the community is ready—not just to be heard, but to be heeded.