The escalating impacts of climate change on the African continent are alarming and made worse by indiscriminate human extraction activities. The UN’s 2020 Emissions Gap Report underscores the urgency of acting to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, revealing a trajectory towards a 3°C temperature increase within a century, far exceeding the Paris Agreement’s goals.

Climate change court cases on the continent additionally show the urgent need for action, emphasizing that for Africa, the consequences of inaction will be dire. These court cases emphasise the role of governments in holding polluters accountable, as well as ensuring their policies and laws put people and planet first. Without furthering and clarifying the law, environmental justice and human rights standards will suffer.

At this critical juncture, the recent decision by the United Nations General Assembly to seek an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on climate change could not be timelier. This decision shows that there is international recognition for the complex legal features tied to the climate crisis. It further emphasizes that to combat climate change, we need legal certainty on state obligations towards reducing it.

Why African states may not respond to the ICJ

Africa’s complex relationship with the ICJ, and the pressing issue of climate change, converge in a pivotal moment of global governance. In the face of mounting climate challenges, African nations could find themselves at a crossroads.

On one hand, the ICJ’s advisory opinion provides a potential opportunity for there to be legal accountability for the historic emissions of fossil fuel producers and polluters.

On the other hand, historic suspicion of international legal forums and competing developmental priorities complicate Africa’s embrace of international legal mechanisms. Despite the urgency of the climate crisis, Africa’s engagement with the ICJ’s advisory opinion on state obligations in respect of climate change is set to be surprisingly tepid. Why is this the case?

The relationship between the ICJ and Africa has often been characterized by a complex and nuanced history. From colonial legacies to struggles for sovereignty, the continent’s interactions with the ICJ have been shaped by a myriad of factors.

Distrust of International Legal Bodies

One crucial factor to consider is the historical context of Africa’s relationship with international legal institutions generally. Historically, African voices have been disregarded in global decision-making processes, and African countries were often excluded from the development of multilateral institutions.

This historical exclusion, compounded by the fact that many African nations were under colonial rule when the ICJ Statute was drafted, has fostered a sense of disillusionment and disengagement. During the drafting of the ICJ Statute, most African states were colonies and could only be spoken for by their colonial powers rulers, who disregarded traditional African legal practices as being ‘repugnant to natural justice and humanity’. Many African nations have a deep-seated scepticism towards international legal bodies perceived as Western-centric or biased (the International Criminal Court falls under this category).

This historical distrust should not, however, stand in the way of Africa’s seat at the table of international law in modern times. International institutions like the ICJ have since become more progressive. For example, the court sits 15 judges, three of whom are African judges and three are women. The court has rendered landmark and applaudable decisions, and opinions curtailing potential acts of genocide, protecting the right of states to self-determination and issues of state sovereignty.

Complicity of African States in Fossil Fuel Projects

The reluctance of some African states to fully engage with interpretations of accountability regarding climate change may stem from their perceived ‘right to development’, particularly in the context of fossil fuel production (gas). Many African countries are still committed to the false notion that fossil fuel extraction and production are crucial drivers of economic growth and development. In their view, any restrictions or duties imposed on their ‘fossil fuel’ activities may be perceived as intrusions on their sovereignty and developmental aspirations.

There is currently a “dash for gas” reserves all across the continent, signalling a flawed but pseudo gas renaissance which is wrongly being promoted as a transition fuel. In one case, Africa’s largest oil producer, Nigeria, has expressed its commitment to continue oil production as a means of economic development and poverty alleviation. Nigerian officials argue that the country has the right to exploit its natural resources for the benefit of its citizens and that any attempts to curtail its fossil fuel activities would be unjust and counterproductive to its development goals.

The AU 2063 Agenda places its main focus on this developmental arm, elevating, ‘sustainable development’ as its top aspiration. Whilst climate adaptation and resilience are mentioned, this is lost due to the competing emphasis on economy building, and realisation of industrialisation. In this context, the ICJ’s advisory opinion on climate change may not always be perceived as a top priority.

Non-Binding Nature of ICJ Advisory Opinions

The perceived limitations of the ICJ’s advisory opinions may also play a role in shaping African states’ engagement. While these opinions provide valuable legal guidance, they are non-binding and lack enforceability mechanisms. In the face of urgent and tangible threats posed by climate change, African nations may prioritize action-oriented approaches that deliver concrete results over legalistic interpretations.

There is an argument to be made that this perception is false; whilst the advisory opinion is non-binding, it still has legal authority and is a persuasive force. Moreover, academic writings have alluded that the court’s opinions are essentially obligatory for the requesting body and qualify as authoritative statements of law. For instance, the landmark opinion on the Construction of a Wall in Palestine (2004) and the Chagos Archipelago decolonisation case (2019) carried significant weight, compelling compliance from UN member States regarding their international legal duties and obligations. The ITLOS special chamber found that the Chagos Advisory Opinion had legal impacts and clear consequences for the legal status of the Chagos Archipelago.

What Now?

Unfortunately, there is little time for African States to engage the ICJ. Countries have until the 22 March 2024 to make their submissions in terms of the relevant Rules of Court. Will the countries that do, seize the opportunity to lead the charge for climate justice? Only time will tell as Africa navigates the complex terrain of international law, climate action, and state responsibilities in respect of climate change impacts.

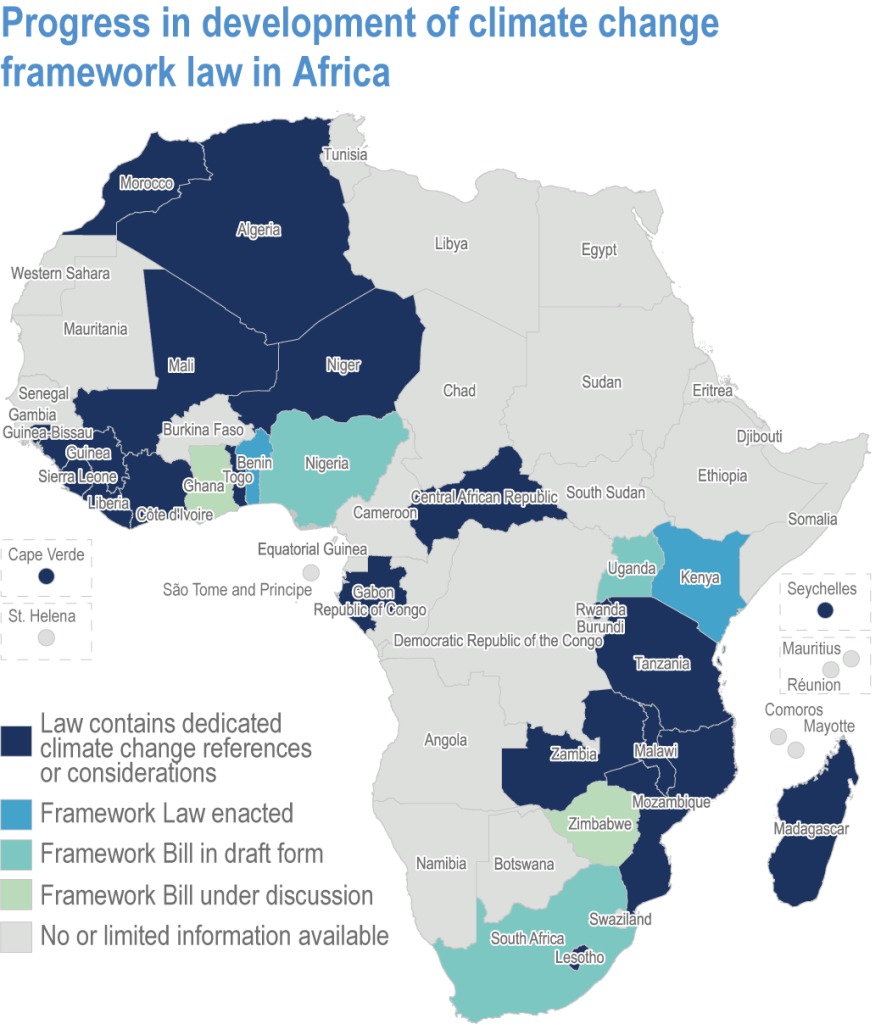

In the meantime, States should continue to develop their national laws in alignment with human rights and climate justice obligations. They should be responding to the climate emergency. A 2022 report by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows that there is only fragmented development of domestic climate change frameworks across African countries. This is something that needs to shift in the coming years.