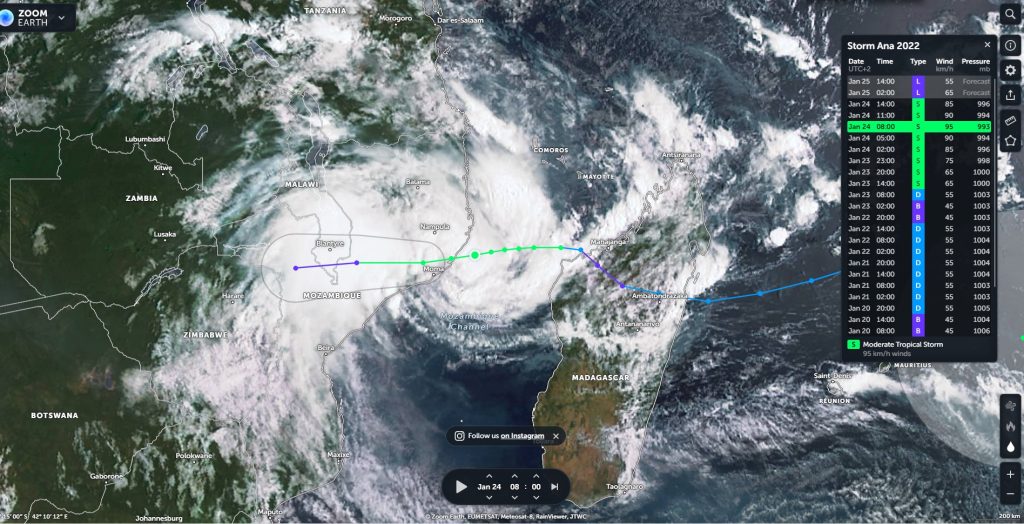

As of yesterday, forty-seven people were declared dead after Tropical Storm Ana swept through the heart of Madagascar, before making its way across Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Another storm is expected. Whereas a few years ago, the link between extreme events and climate change may have been brushed under the carpet, these links are becoming a common narrative.

“Mozambique and other southern African countries have been repeatedly struck by severe storms and cyclones in recent years that have destroyed infrastructure and displaced large numbers of people.

Experts say the storms have become stronger as waters have warmed due to climate change, while rising sea levels have made low-lying coastal areas vulnerable.”

“Death toll rises to at least 12 after tropical storm Ana sweeps through Mozambique, Malawi” – News24

As the global climate crisis worsens, an increasing number of people are being forced to flee their homes due to natural disasters, flooding, droughts, and other severe weather events. The impacts of climate change have deprived many people of daily food, clean water, and the necessities to maintain their livelihoods, which has in turn, forced them to seek safety elsewhere.

While many people displaced by climate events find refuge within their own country’s borders, some are forced to go abroad. In 2020 alone, 30.7 million people were displaced because of environmental disasters, notably linked to climate change. The World Bank estimates that approximately 140 million people will be displaced globally due to climate-related reasons by 2050.

The effects of climate change are expected to be particularly pronounced in Africa, where rising temperatures, irregular rainfall patterns, and high vulnerability to extreme weather events will continue to exacerbate conflict and harm local and regional human, economic, and environmental security. The continent’s high dependence on rain-fed agriculture and pastoralism means that livelihoods and food security are inextricably linked and affected by long-term or sudden environmental changes and natural disasters.

In the Sahel region, for example, temperatures are rising 1.5 times faster than the rest of the world, and climate-related impacts are increasing competition for resources and, in turn exacerbating conflicts. Yet, so far, national and international responses to this challenge have been limited, and protection for the people affected remains inadequate.

Problems with the definition of climate refugees

The term “climate refugees” has been coined to describe the increasing large-scale migration and cross-border movements of people because of weather-related disasters. However, the legal rights and status of those who move in the context of disasters, climate change, and environmental degradation remains unclear and insufficient.

Under international law, “refugees” are people outside their countries of origin who have fled because of a well-founded fear of persecution. Since most people remain within their countries or are people whose cross-border movements are taken solely as a result of environmental harm and not persecution, they fall short of the international legal definition of a “refugee”. Thus, they are not afforded any special protections under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its Protocol.

This leaves a gap in the protection of such people, as there is neither a clear or agreed upon definition for persons who move for environmental or climate-related reasons, nor an international treaty protecting them – leaving them in legal limbo. The lack of lawful migration opportunities forces many of those moving for climate-related reasons to do so without authorisation and at risk of exploitation or abuse. And their precarious legal status makes it difficult for people to re-establish and support themselves once they have fled.

Policy and legal responses

Investment in legal, financial, technological, and capacity-building support tools are vital to help fortify and protect climate-vulnerable communities and address climate-induced displacement moving forward.

Legal alternatives may include extending the Refugee Convention to include displacement from environmental harm (note many experts are highly opposed to this), or establishing guiding principles on displacement from environmental harm (similar to the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement).

Africa is, in fact, already one step ahead at the regional level. As the African Union’s Kampala Convention for Internally Displaced Persons is the world’s first, and to date only, binding agreement for protecting people internally displaced by natural disasters.

In addition, policy alternatives that address climate-related displacement could include migration agreements between different nation-states. This can already be seen in West Africa, where there is a dedicated framework for nomadic groups that authorises the cross-border movements of pastoralists and their livestock in need of water and pasture.

In East Africa, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) also recently adopted a new Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, which specifically allows those at risk of natural disasters and climate change to enter their neighbouring country following, or to avoid, the impacts of a climate disaster.

Human rights law could also be used as a tool to specifically address displacement linked to climate change moving forward. The recent historic ruling of the UN Human Rights Committee in Ioane Teitiota v. New Zealand was the first ruling on a complaint by an individual seeking asylum from the effects of climate change. The Committee determined that countries may not deport individuals (non-refoulement) who face climate change-induced conditions that violate the right to life. Furthermore, under human rights law, States bear positive obligations which require them to take measures to prevent displacement and to relocate those adversely affected by climate change and related disasters.

“The climate crisis is becoming a human crisis”, said the United Nations’ Refugee Agency (UNHCR), at COP26 in Glasgow. Forced displacement is among the most devastating human consequences of climate change and shows the deep inequalities in our world. Countries and communities with fewer resources and less capacity to build climate resilience are currently facing the worst impacts.

As climate change intensifies, so will the threats to people’s safety, security, and dignity, which is only worsening poverty and access to food, water, and other necessities. We urgently need new legal tactics, innovation, funding, and political will to prevent and minimise climate-related displacement and its effects on its oftentimes forgotten victims.

***

*Mareike was an International Fellow at Natural Justice.